This blogpost is a mid-week update on the progress split between a minor update on the dungeon-generator and more research-related talk that is more relevant to the module itself.

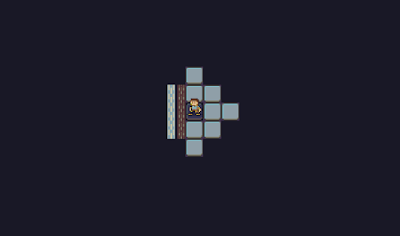

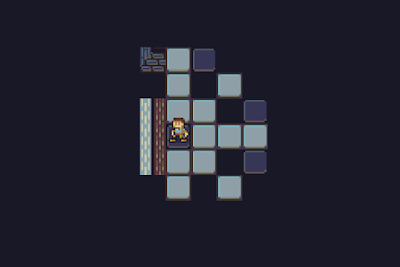

To start with, the generator has most of its systems in place now, with the proper infrastructure set up to ensure that tiles are usable objects with the most basic set of properties we need to use them efficiently, but most importantly is I managed to spend a couple of days writing and then rewriting asset loading functionality.

The generator now has the ability to instantiate a special AssetLoader script that is designed to handle my template for tilesets, and can also handle more custom tilesets like the door and ladders for now. With this support it has become very convenient to switch between lit and unlit tiles without having to write new code to poll the logic of when we should do that and what specific graphics etc, now tilesets can inherently flip their tiles from lit to unlit as needed through one method.

From a research perspective, building on the latest class presentations that ask us to think about the game in a more broken down perspective and analyze the particulars within each mechanic, I've been thinking about how to break down what can be considered a modest interpretation of the core roguelike experience:

The player approaches a small room with a ladder going down to the next floor. In front of it stands a goblin with a club and shield. The music has changed into a more combat-esque setting. Unsure of whether or not he'd win in a melee fight right now, the player backs away and goes to take out a bow instead of his sword.

1) Input

The player typically uses the keyboard for input on a roguelike, not often the mouse. As such, we see input from the arrowkeys or WASD or other keyboard-format equivalents being used for directional controls. Every in-game 'turn', a new instant-effect / short-term command is given to the player's character.

2) UI

The player needs to have fluent and easily identifiable access to the user interface and all that it provides. To this end, buttons like Inventory, Options, and more rogue-like-specific options like examining need to be clearly allocated to a convenient location. It's likely that in a more modern setting like this prototype that they would be accessible via mouse, rather than overcomplicating a modern gaming scene with mandating keyboard controls for *everything*.

(Obviously some people like this, but a large argument of this prototype is the experiment of finding a balance between the good old and the bad old)

3) The Environment

The player cannot see the whole environment at any one time. They see only some area around them, which might depend on whether or not they have a light source. The player spots a critical threat to their current run of the game by being able to see it in time to formulate an appropriate reaction.

4) The Enemy

The enemy is as complex as the player in a roguelike game. They are bound by the same rough principles of logic within the gameworld. If something sets the player on fire, it generally sets the monsters on fire too (Unless they are specifically immune to it). The enemy will not spot the player any faster than the player can spot them unless it had to be intentionally given such an ability (night-vision, a great field of vision in the first place, etc)

For a final piece relating to recent module lectures, we have the idea of game progression, something that is very unique in a Roguelike game.

The progression of a rogue-like can both be the sole target and yet can be the utmost trivial accomplishment ever. Rogue-likes are traditionally very difficult, forcing you to move ever-onward in the hunt for resources and equipment. To die is to be expected, and to not die is rare. Perhaps then the true progress of the game is your overall accomplishments, not your ability (or lack thereof) to beat the final task the game hands to you.

That's all for this blog update, once there's a working prototype of the dungeon-generator, I'll be back.